1) The setting: a matchup that became an anatomy lesson

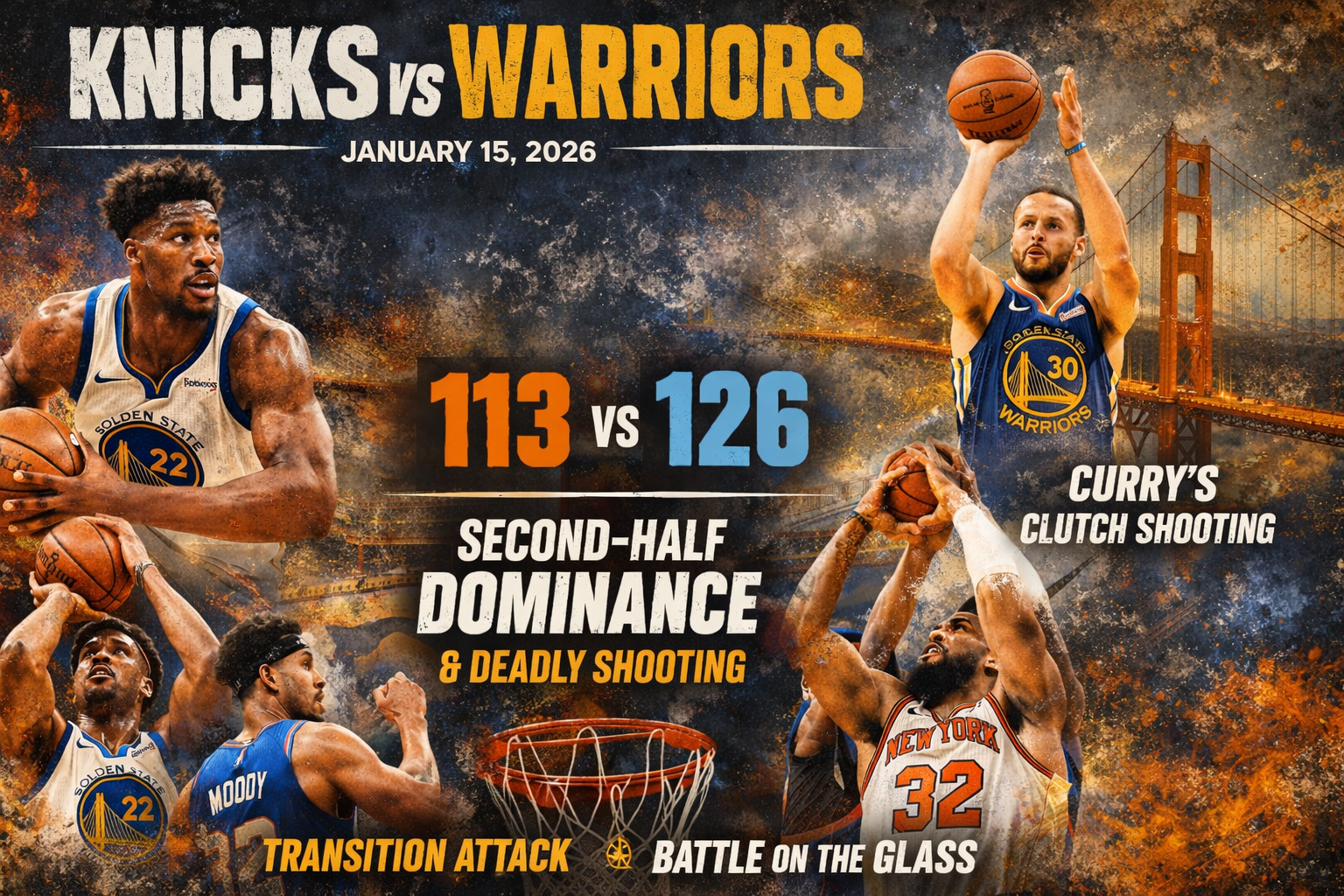

The latest Knicks vs Warriors meeting landed at Chase Center on January 15, 2026, and by the final horn it looked less like a single game and more like a tutorial in how modern NBA offenses separate good process from cosmetic advantages. Golden State won 126-113 after losing the opening rhythm battle, then steadily bending the game toward its preferred terrain: halfcourt decision-making, spacing that stretches help to the breaking point, and shot quality that holds up even when the opponent finds extra possessions.

New York did not arrive at full strength. Jalen Brunson was out with a right ankle sprain, forcing the Knicks to rewire their offense on the fly and lean on secondary creation. That context matters, but it does not fully explain the shape of the loss. The Knicks actually won several of the “effort” margins that often travel well: they scored 22 fast break points to Golden State’s 10 and grabbed 15 offensive rebounds to the Warriors’ 10. In many games, that combination is a recipe for control.

Instead, the Warriors produced the more valuable currency: elite shotmaking supported by repeatable shot creation. They finished at 54% from the field and hit 20 threes (44%), outpacing New York’s 46% shooting and 14 made threes (37%). When one team is scoring that efficiently in the halfcourt, extra possessions stop feeling like leverage and start feeling like a requirement just to keep up.

2) How the game flipped: from early Knicks shotmaking to Warriors structure

The Knicks’ best stretch came early. They opened with a barrage from deep and built a 31-14 lead, a burst fueled by confident pull-ups, quick kick-outs, and the kind of early-clock threes that can flatten a defense before it has time to communicate. But early leads can be fragile when they are built more on shot streaks than on forcing the opponent into bad shots.

Golden State’s response was revealing. Rather than panicking into isolation possessions, they tightened the connective tissue that makes their offense stable: better spacing on drives, earlier decisions against help, and more purposeful screening that forced New York into rotations instead of straight-line containment. The Warriors stabilized by halftime, then took over the third quarter with a burst driven by Curry’s gravity and a quicker tempo in their halfcourt execution.

This was also a 17-point comeback, matching the largest lead either team held in the game. The significance is not the number itself, but the method: the Warriors came back by improving the quality of their possessions, not by simply trading tough shots.

3) The Warriors’ offensive engine: Butler as the pressure point, Curry as the closer

The headline names were obvious, and the box score supports it. Jimmy Butler III scored 32 on 14-of-22 shooting, adding eight rebounds and four assists. Stephen Curry finished with 27 points and seven assists on 10-of-17 shooting. But the real story is how their roles complemented each other.

Butler’s value in games like this is that he turns defensive “almosts” into breakdowns. Even when the first defender stays attached, his downhill drives force help to commit. That is when Golden State’s spacing becomes a trap: help arrives, the ball moves, and the next rotation is late. Those are not highlight plays, but they are the plays that create 20 made threes without requiring contested shot luck.

Curry then takes over the part of the game that breaks opponents mentally: the phase where the defense has already spent two quarters rotating, and any hesitation turns into a dagger three or a quick two. New York trimmed the margin late, but Curry’s fourth-quarter shotmaking reasserted control and restored separation when the game threatened to turn into a scramble.

4) Moses Moody and the spacing tax: why one hot shooter changed the geometry

Moses Moody’s line is the kind that looks like a bonus until you trace its tactical effect. He scored 21 points and went 7-for-9 from three. That is not just “extra points”; it is spacing that eliminates defensive shortcuts.

When a wing is shooting like that, the defense cannot “tag” the roller as aggressively, cannot stunt and recover as freely, and cannot send the same volume of help at Butler’s drives. Every time New York shaded one step too far toward the ball, Moody made the punishment immediate. In practical terms, that means the Knicks had to defend more honestly, and honest defense is exactly what Golden State is built to pick apart with screening, passing angles, and relocation.

This is also how the Warriors won despite losing the fast break points battle. If the Knicks are scoring in transition but the Warriors are scoring efficiently against set defense, the math starts to tilt toward Golden State because halfcourt points are easier to reproduce possession after possession.

5) New York’s offense without Brunson: good options, fewer easy ones

Without Brunson, the Knicks needed creation from a committee. They got real production: OG Anunoby scored 25, Miles McBride scored 25, and Mikal Bridges added 21. Karl-Anthony Towns finished with 17 points and 20 rebounds, a massive workload on the glass. On paper, that is enough scoring to win many nights.

The issue was not a lack of talent. It was the difficulty level of the offense. Brunson is the type of guard who manufactures “easy twos” and forces the defense to collapse late in the clock. Without him, New York leaned more on jump shot creation and quicker decisions, which can be fine, but also tends to produce a flatter diet when the opponent can stay connected.

The Knicks did find two valuable pathways:

- Transition: 22 fast break points suggests they were able to run and convert before Golden State’s defense set.

- Second chances: 15 offensive rebounds gave them extra opportunities to score without having to beat a set defense from scratch.

But those pathways need to be paired with halfcourt efficiency to beat a team that shoots 54% and makes 20 threes. New York’s halfcourt possessions were simply more work, and the Warriors’ were more surgical.

6) The defensive chess match: turnovers stayed normal, shot quality did not

One of the most telling pieces of the team stats is that this was not a wild, turnover-driven game. The Knicks had 13 turnovers and the Warriors had 12, basically a wash. That means Golden State did not win by chaos.

They won by forcing New York into harder shots while generating cleaner ones themselves. A few indicators point in that direction:

- Golden State shot better overall and from three.

- The Warriors produced more stocks: 7 steals and 6 blocks versus 3 steals and 2 blocks for New York.

- Points in the paint were close (48-44 Warriors), suggesting Golden State did not abandon rim pressure even while bombing threes.

This is the modern profile of a strong offense: threes plus paint touches, with enough passing to make the defense choose which kind of damage it prefers.

There was also an edge-of-the-line physical moment that mattered emotionally: Draymond Green was assessed a Flagrant 1 after a tripping play involving Towns. The bigger takeaway is not the incident itself, but how Golden State maintained control after stoppages and momentum swings. Teams that are truly organized tend to return to their principles. The Warriors did.

7) Why Golden State’s shot profile was sustainable

It is tempting to reduce a 20-for-45 three-point night to shooting variance. But even the raw distribution shows a sustainable concept: volume created from advantage, not volume created from hope. Golden State did not simply fire early-clock pull-ups; they combined drive pressure (Butler), off-ball gravity (Curry), and reliable release valves (Moody, Podziemski) to force rotations, then punished the rotations.

Brandin Podziemski’s 19 points on 8-of-9 shooting is a perfect example of “secondary efficiency.” When your secondary scorer is finishing at that rate, it usually means he is getting shots created by the structure, not by self-generated hero possessions. That is how a team shoots 54% without living at the free throw line.

8) The result, in one sentence: the Warriors won the halfcourt game by a mile

New York fought for extra possessions and found transition chances. Golden State won the possession-by-possession shot quality battle so thoroughly that the Knicks’ advantages became supporting details instead of deciding factors. The final score, 126-113, reflects that truth: the Warriors were more efficient, more spaced, and more decisive for longer stretches of the night.

9) What it means going forward

For Golden State, this game reinforced a winning formula that does not rely on perfect health or perfect shooting nights:

- A downhill creator who forces help (Butler).

- An elite movement shooter who closes quarters (Curry).

- At least one wing who makes the defense pay for loading up (Moody).

- Secondary finishers who keep the floor balanced (Podziemski and the supporting cast).

For New York, the game was a reminder of how thin the margin becomes when a primary creator is missing. The Knicks have enough two-way talent to compete anywhere, but against an offense this clean, they need either a stabilizing on-ball advantage (which Brunson usually provides) or a defensive performance that takes away the opponent’s first option. They did neither for long enough, and Golden State’s structure eventually turned the game into a math problem New York could not solve.