The news, stripped to its mechanics

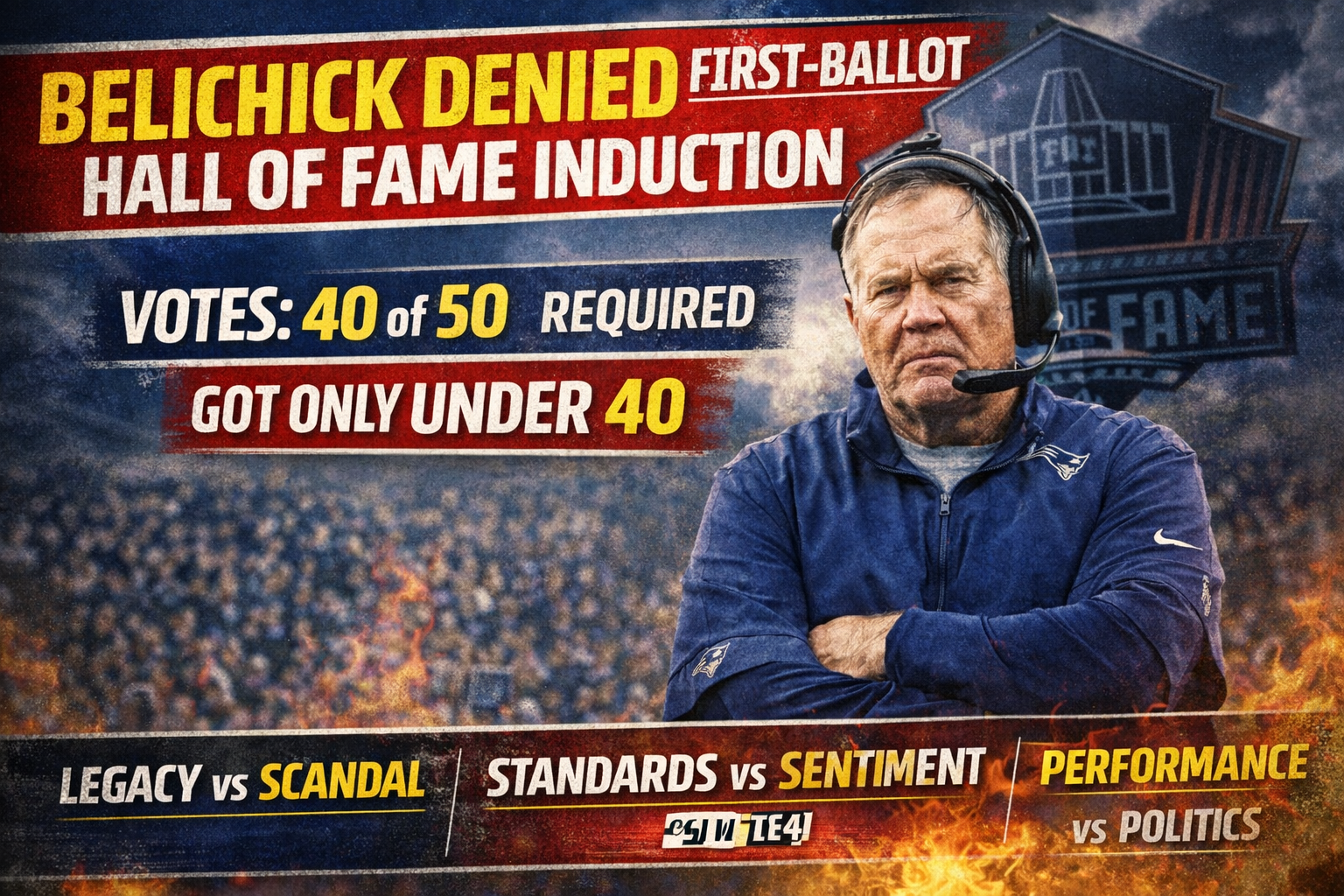

Multiple reports indicate Bill Belichick will not be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on his first ballot, falling short of the 40 of 50 votes required.

That outcome is especially jarring because Belichick was identified as the coaches category finalist after the Coach Blue-Ribbon Committee process, which typically signals a clear runway.

The Hall is expected to announce the Class of 2026 during NFL Honors on Feb. 5 in San Francisco.

So what actually “happened latest” is not a game result or a signing. It is a governance event: a legendary coach hit the limits of a voting institution designed to turn a career into a verdict.

Why this became controversial: Belichick is a stress test for the Hall itself

Belichick’s résumé is almost uniquely built to overwhelm any performance-only framework: six Super Bowl titles as a head coach in New England, plus two more rings as a Giants defensive coordinator, and a coaching win total that places him among the all-time leaders.

If the Hall were a pure measurement of on-field value, he is a first-ballot outcome with room to spare.

The fact that he was not selected reveals what the Hall has always been, but rarely has to admit out loud: a hybrid of achievement recognition and moral arbitration.

The real question voters answered

Voters were not deciding whether Belichick was great. They were deciding what “great” is allowed to mean inside the Hall’s brand.

Reports point to Spygate and Deflategate as residual weight in the room, including the idea that Belichick should “wait a year” as a form of penance.

That framing matters because it converts the ballot from recognition into sentencing. The vote becomes less “did he change football” and more “has the institution forgiven him.”

This is why the reaction was so visceral. The backlash was not only from fans; it was also from prominent players and media voices who treat the Hall as the sport’s constitutional record, not a court of reputation.

The procedural irony: a one-year eligibility rule meets a long memory

Belichick’s eligibility window is itself a product of a rule change that reduced the waiting period for coaches to one year out of the league.

That reform is meant to modernize the Hall, keeping it connected to the current sport. But it also creates a collision: the shorter the wait, the hotter the reputational residue.

For some voters, five years of distance can cool controversy and clarify contribution. One year does the opposite: it invites the vote to become a referendum on how the last chapter felt rather than what the full book says.

What this exposes about “first ballot” as a concept

“First ballot” is not a ranking of greatness. It is an institutional signal of uncomplicated greatness.

Belichick is great, but complicated:

- He represents the most dominant modern dynasty and the sharpest edge of competitive rule-bending narratives.

- He is the architect of systems, not a public-facing charisma figure.

- His legacy forces voters to weigh “how you win” alongside “how much you win.”

When the Hall delays a candidate like this, it is effectively declaring that the Hall is not just a museum of outcomes. It is a museum of acceptable stories.

Why the football case is still overwhelming

Even if you treat scandals as legitimate context, the football value remains enormous:

- The Patriots’ two-decade run was built on weekly adaptability: opponent-specific plans, situational mastery, and ruthless exploitation of mismatch and tendency.

- Belichick’s edge was not one scheme. It was an operational model: roster churn, matchup-driven game planning, and defensive multiplicity that kept evolving as the league changed.

That matters because the Hall is supposed to honor what moved the sport forward. Belichick did. The league’s modern emphasis on situational decision-making, sub-package flexibility, and game-plan variance is partly a response to what his teams normalized.

The reputational counterargument, taken seriously

The best argument against immediate induction is not “he cheated.” It is “the Hall must defend its standards.”

If voters believe that institutional integrity is part of the Hall’s mission, then the most powerful candidates become precisely the ones you can least afford to wave through, because the Hall’s credibility is set by its hardest cases.

But this stance has a cost: it creates inconsistency unless the Hall openly defines what kinds of conduct delay induction and for how long. Without that, “standards” can become “vibes,” and the process looks political even when it is sincere.

The UNC subplot: how current work colors legacy votes

Belichick’s recent move into college coaching at North Carolina, and the widely reported struggles of his first season, add another layer of recency bias to a vote that is supposed to be career-spanning.

It should not matter, but human committees do not vote in vacuums. A living, evolving figure is harder to freeze into an artifact.

What comes next and what it will mean

Belichick being delayed does not change where history will land. It changes what the Hall is signaling about itself right now.

If he goes in later, the Hall will likely frame it as a normal sequencing outcome. The public will frame it as an ideological statement, because the first vote was already interpreted that way.

The longer the Hall stays silent about standards, the more every future ballot becomes a referendum on the process rather than the people.

Belichick’s case, more than almost any modern candidate, demands that the Hall decide what it is:

- A record of competitive achievement

- A guardian of the sport’s moral narrative

- Or an uneasy blend that needs clearer rules to avoid looking arbitrary

Right now, the message is clear even if the Hall never says it: greatness can be delayed when the institution is still arguing with the story.